Economic signals for deforestation in Brazil

Diego Flaresso de Oliveira, Senior Environmental Analyst, GSS Carbono e Bioinovação

The Cerrado is a unique and important ecosystem for Brazil. Its high species diversity, as well as the presence of many endemic species, makes it a hotspot for global biodiversity conservation. Nonetheless, the expansion of Brazil’s agricultural frontier has intensified deforestation in this biome, with significant losses of its original forest, making it the most deforested vegetation in the country. In addition, deforestation here also opened the gates for agriculture and cattle ranching to penetrate the southern Brazilian Amazon, a region bordering the Cerrado biome.

The evolution of this scenario coincides to a large extent with the region's increased production of soy, a commodity for which Brazil is now the world's second largest producer, accounting for approximately 35% of global production.

Despite Brazil's strict environmental regulations requiring landowners and farmers to comply with certain land-use and conservation standards – the latest milestone being law 12,651 of May 2012, which enacted the Forest Code – enforcement and real impacts of such rules remain elusive. The state’s failure to enforce environmental laws favors deforestation and unsustainable practices that, over the years, have brought a significant loss of original plant cover.

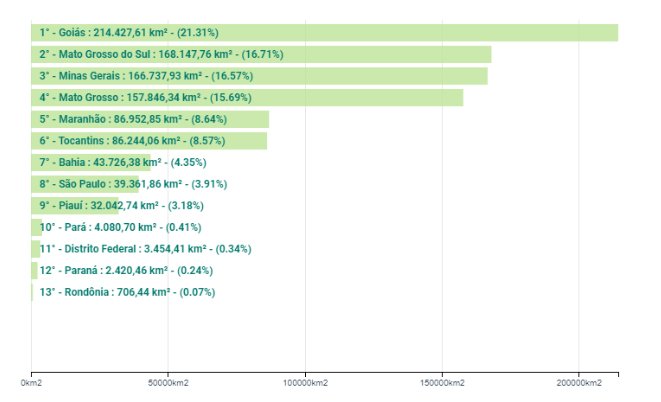

Figure 01 – Accumulated deforestation increase in the Cerrado, by states¹

According to the logic of REDD+ (Reducing Emissions of Greenhouse Gases from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) carbon projects, deforestation occurs in two modalities: planned or unplanned. Both have common motivations, including the drive to increase productive areas, but they work differently, and are influenced by different factors.

Planned deforestation – commonly referred to as APD, or avoided planned (i.e., designated and sanctioned) deforestation, in REDD+ projects – is certainly responsible for the largest share of deforestation, since most farms and productive areas are minimally legalized and commercially legitimate. The driving force behind "legalized" expansions of the agricultural frontier is the intent to increase production, when a larger area means more soy sold and more money in return. In the Cerrado, indeed, only 20% of a farm needs to be set aside as a Legal Reserve of native vegetation (the requirement rises to 35% for farms inside the boundaries of the Legal Amazon).

Figure 02 shows the huge spread of areas planted to soy in the past 20 years in Brazil. Since more production and financial returns are driving this quest for expansion, the best countermeasure is to offer a proportional and fair remuneration for non-deforested areas. Once native vegetation becomes an asset – enough of an income source to make it reasonably and justifiably more profitable to keep it intact than to clear it – the Cerrado will be preserved.

We know that the Cerrado, along with every other parcel of native vegetation, plays a fundamental role in providing a broad range of ecosystem services to everyone on the planet. Unfortunately, no mechanisms have been structured to measure and to value those services to the point of justifying their preservation. The tool that has come closest to this ideal is the Carbon Credit, in which the quantification of carbon stored in an area generates credits for 'non-emissions' resulting from foregone deforestation.

Figure 02 – Comparison of areas planted to soy in Brazil

The truth is that maintaining native vegetation (which means preventing everything from naturally occurring fires to illegal deforestation) has a cost, and someone must foot the bill. It is in the interest of all who benefit from the presence of this vegetation to pay people closest to these areas (who have been the main agents of deforestation) to protect them and keep them in the best possible condition. The additional income can be invested to increase productivity, as well as to improve infrastructure to transport the production. In this regard, Brazil is far behind its North American competitors.

The second modality, unplanned deforestation – commonly referred to as AUD, avoided unplanned (i.e., unsanctioned) deforestation, in REDD+ projects – is criminal in nature and difficult to control. Taking advantage of poor enforcement of Brazil's often weak environmental regulations, corruption, and a weak land-tenure system, it is difficult to hold soy farmers accountable for such violations.

Implementing new, more efficient rules, enforcing environmental regulations, and strengthening environmental enforcement institutions, will all be crucial to reduce illegal deforestation. One adverse effect of greater environmental control, though, is that many companies and major polluters take steps to evade or outwit negative impacts on their own production activities.

Companies that "export" their dirty production to other regions with no emission-reduction mechanisms, in order to escape stricter climate policies at home, are committing Carbon Leakage. They continue to sell to developed markets with stricter climate policies, having gained an unfair competitive advantage over local producers in these regions. The effect of climate policies is thus reversed, benefitting polluters, penalizing those who price their carbon emissions, and skewing competition.

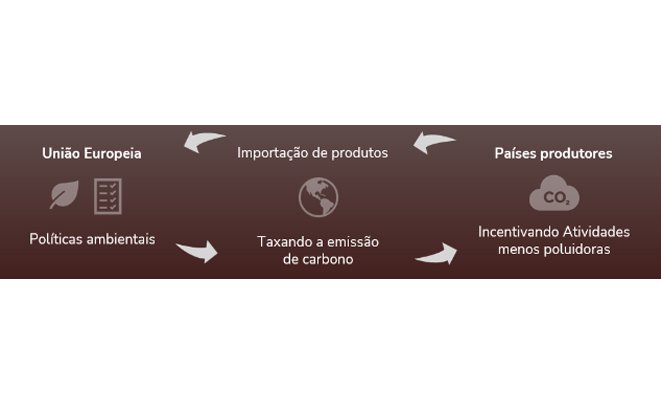

Initiatives to create economic mechanisms focused on climate change and biodiversity are emerging in a number of markets, through incentives for farmers to adopt sustainable practices. Leading this movement is the European Union, which plans to restrict goods sourced from areas with deforestation (whether sanctioned or not) as well as to tax products that have not offset their carbon emissions, thereby avoiding Carbon Leakage. The global nature of climate change impacts means that sustainability policies have also become increasingly internationalized, extending beyond the borders of developed nations.

Figure 04 – Scheme proposed by CBAM³ (2022)

Complementary solutions are being developed to increase transparency and traceability in the soy supply chain and to identify cases of deforestation. This can be done through satellite imagery and certification mechanisms provided by the ProTerra Foundation, the Soybean Innovation Lab and the Roundtable on Responsible Soy (RTRS). Soy certification is important to enable consumption chains to favor consumption of their sustainable, deforestation-free products.

Mapping the entire soy supply chain and using monitoring technologies will be important tools to build an enabling environment for sustainable soy production. Overall, reducing deforestation in the Cerrado requires collaborative efforts by many different stakeholders, including government, civil society, and the private sector. Soy production is critical to the industry’s future and to the sustainability of global food systems, so providing incentives for policymakers, farmers, investors, and other stakeholders to support and invest in sustainable production practices will be fundamental to achieve a more equitable, resilient, and sustainable future.

References:

¹ http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br/app/dashboard/deforestation/biomes/cerrado/show - Data from 12/14/2022

² https://www.globalforestwatch.org/map/-

³ https://commission.europa.eu/index_en

⁴ https://www.proterrafoundation.org/

⁵ https://www.soybeaninnovationlab.illinois.edu/

⁶ https://responsiblesoy.org/?lang=en